Kidney transplantation, standing as the definitive treatment for End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD), represents far more than a surgical procedure; it is a life-altering odyssey demanding exhaustive preparation, intricate surgical execution, and a demanding, lifelong commitment to recovery. The process begins not in the operating room, but with an intense, multi-faceted evaluation designed to rigorously assess the suitability of both the recipient and the potential donor. For the recipient, this involves a complete overhaul of their medical records, extensive imaging studies, and a battery of tests to confirm that the patient is physically capable of withstanding major surgery and the subsequent regimen of immunosuppressive drugs. Conditions like active infection, recent cancer history, or uncontrolled cardiac disease can temporarily or permanently disqualify a candidate, as the risks associated with transplantation would outweigh the potential benefit. This initial, uncompromising selection phase sets the foundation for the success of the entire treatment arc.

The process begins not in the operating room, but with an intense, multi-faceted evaluation designed to rigorously assess the suitability of both the recipient and the potential donor.

Crucially, the evaluation heavily focuses on immunological compatibility to minimize the risk of hyperacute and acute rejection. This requires sophisticated tissue typing (HLA matching) to compare Human Leukocyte Antigens between the donor and recipient, alongside a cross-match test to check for pre-formed antibodies in the recipient’s blood that could immediately attack the donor organ. While perfect HLA matching is rare, minimizing the mismatch is a primary goal, particularly in deceased donor programs. For living donors, the process is equally stringent, involving a complete health screen to ensure the donor can safely live with one kidney and a deep psychological assessment to confirm the voluntary, non-coerced nature of their decision. The meticulousness of this pre-operative immunological workup is the silent determinant of the graft’s initial survival.

Immunological Meticulousness: HLA Matching and Cross-Match Testing as Determinants of Graft Survival

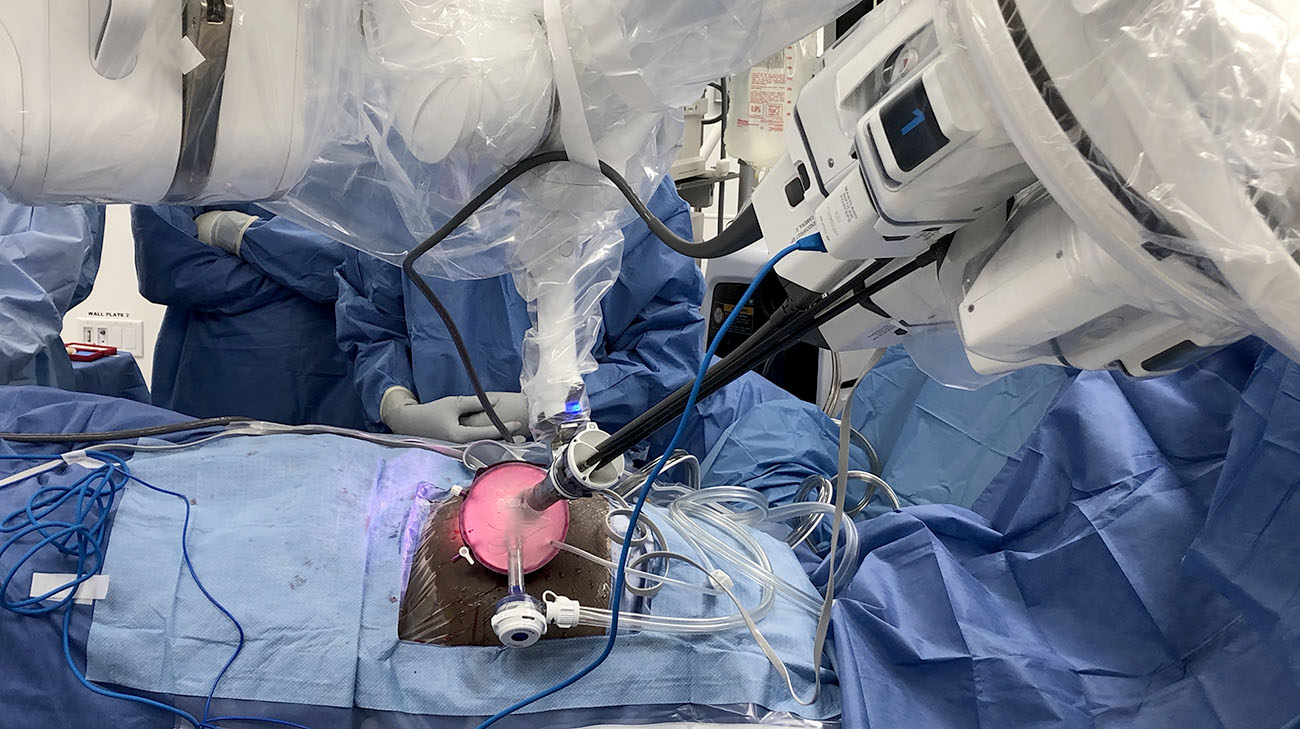

Once a suitable donor is identified—whether living or deceased—and the recipient is medically cleared, the clock starts ticking, often under extreme pressure in the case of a deceased donor. The surgical procedure itself is rarely a simple removal and replacement. The recipient’s native, failed kidneys are typically left in place unless they are causing severe problems (like uncontrolled hypertension or recurrent infection). The new donor kidney is usually placed in the iliac fossa (lower abdomen), allowing easier access to the major blood vessels, specifically connecting the renal artery and vein to the recipient’s iliac artery and vein. The final, critical step is connecting the donor ureter to the recipient’s bladder. This entire procedure is a delicate, vascular reconstruction that requires exceptional surgical precision to ensure immediate, robust blood flow and urinary drainage for the new organ.

The new donor kidney is usually placed in the iliac fossa (lower abdomen), allowing easier access to the major blood vessels

The immediate post-operative period is a phase of intense, high-stakes monitoring, requiring specialized care in the Transplant Intensive Care Unit (TICU). The primary early goal is to confirm that the new kidney demonstrates immediate function, often indicated by prompt, abundant urine production. Some kidneys, particularly from deceased donors, may take several days or weeks to “wake up”—a condition known as Delayed Graft Function (DGF)—potentially necessitating temporary dialysis. Simultaneously, the patient is started on a complex, layered regimen of immunosuppressive medications. These drugs are essential to prevent the immune system from recognizing the new kidney as foreign and attacking it, but they must be carefully balanced to avoid excessive suppression that could lead to dangerous infections.

The Immediate Aftermath: Intense Monitoring for Function and Initiation of Immunosuppressive Therapy

The true challenge of long-term kidney transplantation survival lies in navigating the persistent risk of organ rejection, which remains a threat for the entire life of the graft. Rejection is fundamentally a failure of the immunosuppressive regimen, where the recipient’s T-cells or antibodies recognize donor antigens and mount an attack. Acute rejection episodes, which are more common in the first year, are often treatable with high doses of corticosteroids or specialized antibody therapies. However, Chronic Rejection—a slow, insidious process leading to fibrosis and scarring—is the leading cause of long-term graft loss and is far more difficult to reverse. Constant, low-threshold vigilance, including routine blood tests and often protocol biopsies, is required to catch the subtle biochemical markers of this immune battle early.

Chronic Rejection—a slow, insidious process leading to fibrosis and scarring—is the leading cause of long-term graft loss and is far more difficult to reverse.

The requirement for lifelong immunosuppression is the unyielding condition of graft survival, introducing a cascade of potential secondary health issues that must be managed. Because these drugs dampen the immune system’s overall surveillance capacity, the patient faces an elevated risk of opportunistic infections (e.g., Cytomegalovirus, Pneumocystis pneumonia) and certain types of cancers (e.g., skin cancer, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder – PTLD). Furthermore, many immunosuppressants are associated with metabolic side effects, including new-onset diabetes (PTDM), hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, demanding careful, routine monitoring and aggressive preventative lifestyle management that often includes diet adjustments and increased physical activity.

The Unyielding Requirement: Navigating the Trade-Offs of Lifelong Immunosuppression and Secondary Health Risks

The recovery trajectory for a kidney transplant patient is highly variable but generally involves an inpatient stay of 4 to 7 days, followed by a protracted period of home monitoring. The first three months are the most critical, often requiring frequent clinic visits (sometimes weekly) for blood tests and medication adjustments. Patients must be educated rigorously on the importance of adherence—missing even a single dose of an immunosuppressant can precipitate a rejection episode. Beyond medication, recovery demands significant lifestyle restructuring, including meticulous hygiene to prevent infection, avoidance of large crowds, and immediate reporting of any signs of illness (fever, flu-like symptoms, or localized pain) that could signal infection or rejection. The patient’s active participation is non-negotiable.

The patient must be educated rigorously on the importance of adherence—missing even a single dose of an immunosuppressant can precipitate a rejection episode.

For those receiving a kidney from a living donor, the recovery process has an ethical and medical duality, requiring attention to both individuals. The donor typically undergoes a less invasive surgery (often laparoscopic nephrectomy) and recovers much faster, usually returning to normal activities within 4 to 6 weeks. However, the donor still faces the psychological challenge of recovery and the need for lifelong follow-up to ensure the remaining kidney maintains optimal function and to screen for future health risks. The transplant team is ethically bound to ensure the donor’s well-being is prioritized throughout the process, providing resources and managing the potential emotional complexity of having given a life-saving gift.

The Dual Recovery: Ensuring Lifelong Follow-Up and Psychological Support for the Living Donor

When a kidney transplant fails—which may happen years or decades after the initial surgery—the patient is faced with the profound emotional and medical difficulty of returning to dialysis. Graft failure necessitates a complex medical decision: either removing the failed kidney (graft nephrectomy) if it is causing complications (e.g., uncontrolled hypertension or fever) or leaving it in place if it is silent. Simultaneously, the patient must be re-evaluated and re-listed for a second transplant. The re-transplantation process is often complicated by a higher level of sensitization (more pre-formed antibodies) due to the failed graft, making subsequent cross-matching and finding a compatible donor significantly more challenging. This difficult phase underscores the reality that transplantation is a treatment, not a cure, for ESRD.

Graft failure necessitates a complex medical decision: either removing the failed kidney (graft nephrectomy) if it is causing complications

The role of patient advocacy and support networks in transplantation cannot be overstated. The sheer complexity of the medication schedule, the emotional toll of lifelong vigilance against rejection, and the financial burden require a robust system of support. Patient support groups, transplant coordinators, and dedicated social workers become crucial in managing the non-clinical challenges. Learning to live successfully with a transplanted organ involves mastering self-monitoring, managing the psychosocial weight of immunosuppression, and confidently navigating the complex healthcare system—skills that extend far beyond simply taking pills and attending appointments.

The Essential Non-Clinical Component: Managing the Psychosocial Weight and Financial Burden of Lifelong Care

Ultimately, successful long-term kidney transplantation is less defined by the surgical act and more by the patient’s unwavering adherence to the post-transplant regimen and the continuous, collaborative vigilance of the specialized medical team. The transplant process demands a fundamental shift in the patient’s identity—from someone battling a terminal illness to a proactive participant in their own complex, long-term care. While the graft may not last forever, the transplant provides a dramatic, often life-extending, improvement in the quality of life over chronic dialysis, fundamentally redefining the potential lifespan and freedom of movement for those with End-Stage Renal Disease.

The Unwavering Commitment: Redefining Identity Through Adherence to a Lifelong Regimen

Kidney transplantation is a complex, lifelong commitment; success depends on rigorous pre-operative matching, intense post-surgical monitoring for rejection, and the patient’s unwavering adherence to immunosuppressive therapy.