The pervasive nature of diabetes mellitus as a systemic disease means that its effects ripple far beyond mere glucose dysregulation, ultimately touching nearly every organ system in the body. Among these, the renal system faces a uniquely relentless challenge, where chronic hyperglycemia initiates a cascade of hemodynamic and metabolic changes that progressively compromise the kidney’s intricate filtering units. This gradual but inexorable decline in function, known as diabetic nephropathy, transforms diabetes from an endocrine disorder into a primary concern of nephrology. The management of diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is not merely an optional adjunct to diabetes care; it is an inseparable core component that demands specific, high-level expertise to prevent or dramatically slow the progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD), a devastating complication with immense patient burden and healthcare cost. The sheer complexity of DKD, involving intertwined metabolic, inflammatory, and hemodynamic pathways, necessitates the specialized, granular knowledge that the nephrologist brings to the comprehensive diabetes care team.

The sheer complexity of DKD, involving intertwined metabolic, inflammatory, and hemodynamic pathways, necessitates the specialized, granular knowledge that the nephrologist brings to the comprehensive diabetes care team.

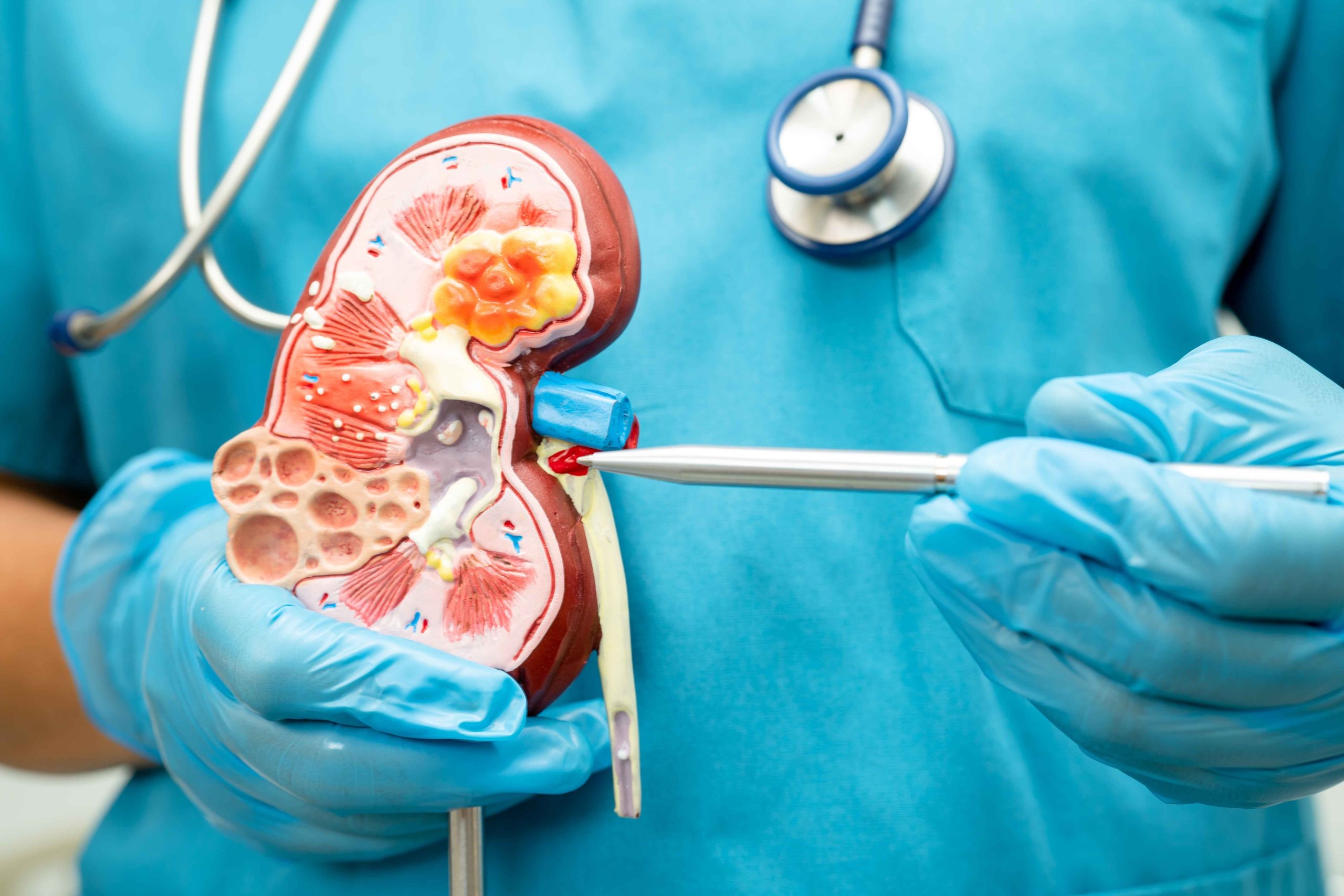

The fundamental damage in DKD begins at the level of the glomerulus, the kidney’s microscopic filtration apparatus. Chronic exposure to elevated glucose levels drives a series of molecular events, including the overproduction of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and the activation of various growth factors and signaling pathways, most notably the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS). These metabolic irregularities precipitate profound structural changes within the kidney: the thickening of the glomerular basement membrane, the expansion of the mesangial matrix, and, eventually, a process known as glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis—in essence, scarring of the renal tissue. The nephrologist’s role here is to not only understand these pathological processes but also to interpret subtle laboratory cues that signal their onset. Early detection is paramount, relying on routine monitoring of the urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) and the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). An elevated UACR, even at the microalbuminuria stage, is a potent alarm bell, indicating compromised glomerular selectivity and demanding immediate, targeted intervention before the damage becomes macro-level and irreversible.

An elevated UACR, even at the microalbuminuria stage, is a potent alarm bell, indicating compromised glomerular selectivity and demanding immediate, targeted intervention before the damage becomes macro-level and irreversible.

Historically, the core strategy for mitigating DKD focused on tight glycemic control, as high blood sugar is the primary instigator of renal damage, and aggressive management of systemic hypertension. The nephrologist’s contribution extended to the nuanced application of RAAS blockade, primarily through Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors (ACEIs) or Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers (ARBs). These medications are unique because they confer renal protection independent of their systemic blood pressure-lowering effect by reducing the pressure within the delicate glomerular capillaries, thereby slowing the progression of albuminuria and the rate of eGFR decline. Determining the correct agent and optimal dosing, especially in the context of already reduced kidney function, requires a specialized understanding of renal physiology and pharmacokinetics, preventing common pitfalls such as an acute, yet manageable, initial drop in eGFR upon initiation. The titration of these cornerstone therapies falls squarely within the nephrology domain, often in consultation with the endocrinologist or primary care physician.

The titration of these cornerstone therapies falls squarely within the nephrology domain, often in consultation with the endocrinologist or primary care physician.

A paradigm shift in DKD management has emerged with the introduction of novel cardiorenal protective agents, significantly expanding the therapeutic arsenal available to the nephrology specialist. The use of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) Receptor Agonists, initially developed as glucose-lowering drugs, has proven to offer dramatic, complementary benefits for the kidney and heart that transcend their effects on blood sugar alone. SGLT2 inhibitors protect the kidney primarily through a hemodynamic mechanism: by inhibiting glucose and sodium reabsorption in the proximal tubule, they increase sodium delivery to the distal nephron. This, in turn, restores the tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism, leading to vasoconstriction of the afferent arteriole and a critical reduction in the intraglomerular pressure, directly counteracting the hyperfiltration injury central to early DKD. The nephrologist guides the use of these agents, considering baseline eGFR thresholds and potential side effects, ensuring that patients receive this crucial, guideline-directed therapy.

The use of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) Receptor Agonists, initially developed as glucose-lowering drugs, has proven to offer dramatic, complementary benefits for the kidney and heart that transcend their effects on blood sugar alone.

The later stages of DKD are defined by worsening renal insufficiency, which introduces a host of systemic complications that require continuous, proactive management by the nephrology team. As the eGFR declines, the kidneys lose their ability to regulate electrolytes, fluid volume, acid-base balance, and bone mineral metabolism. Anemia of chronic kidney disease, driven by reduced erythropoietin production, and mineral and bone disorders (CKD-MBD), resulting from deranged calcium, phosphorus, and parathyroid hormone levels, are routine concerns. The nephrologist manages these intricate disturbances, employing phosphorus binders, active vitamin D analogs, and erythropoiesis-stimulating agents to maintain homeostasis and prevent secondary harm to the patient’s cardiovascular and skeletal systems. This proactive monitoring and intervention are vital, as unchecked complications of CKD significantly elevate morbidity and mortality, particularly from cardiovascular causes.

The later stages of DKD are defined by worsening renal insufficiency, which introduces a host of systemic complications that require continuous, proactive management by the nephrology team.

Beyond pharmacological intervention, the nephrologist is instrumental in guiding necessary lifestyle modifications, particularly the often-challenging aspect of medical nutrition therapy. While overall blood glucose and pressure control are managed broadly, dietary recommendations for advanced DKD become highly specific to renal function. A kidney-friendly diet often requires a targeted restriction of dietary protein to reduce the metabolic load on the compromised nephrons, although this must be balanced to prevent malnutrition. Furthermore, the nephrologist advises on limitations for sodium, potassium, and phosphorus—elements that, when accumulated due to poor clearance, can be life-threatening. Tailoring these dietary restrictions to a patient’s concurrent diabetes management, factoring in their glucose-lowering agents and overall nutritional needs, is a delicate balancing act that requires the deep physiological knowledge of a renal specialist, often working closely with a renal dietitian.

The nephrologist is instrumental in guiding necessary lifestyle modifications, particularly the often-challenging aspect of medical nutrition therapy.

A critical juncture in the management of progressive DKD is the timely and informed discussion regarding renal replacement therapy (RRT). As kidney function deteriorates toward ESRD, the decision to initiate dialysis—either hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis—or to pursue kidney transplantation becomes imminent. The nephrologist is the primary educator and counselor through this deeply personal and medically complex process. They guide the patient through the various RRT modalities, facilitate the necessary vascular access planning (e.g., arteriovenous fistula creation), and coordinate the intricate transition to a life maintained by artificial kidney function. The timing of this transition is crucial: initiating RRT too late is associated with higher morbidity, while starting too early may prematurely impact quality of life. This requires not only medical judgment but also considerable sensitivity to the patient’s holistic needs and preferences.

As kidney function deteriorates toward ESRD, the decision to initiate dialysis—either hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis—or to pursue kidney transplantation becomes imminent.

The success in delaying or averting ESRD in a diabetic patient is rarely the result of a single physician’s effort, but rather the outcome of a coordinated, multidisciplinary care model, with the nephrologist acting as a critical co-pilot alongside the endocrinologist and primary care provider. This team-based approach counters the pervasive problem of therapeutic inertia—the failure to intensify or modify therapy despite clear clinical indicators—by ensuring continuous, guideline-directed pressure on all modifiable risk factors. The nephrologist contributes a singular focus on renal outcomes and the management of CKD complications, translating complex renal physiology into actionable therapeutic plans. This collaboration ensures that treatment decisions are optimized for both glycemic targets and kidney survival, rather than prioritizing one at the expense of the other, which is especially important when prescribing medications with known renal dose adjustments or effects on the kidney.

This team-based approach counters the pervasive problem of therapeutic inertia—the failure to intensify or modify therapy despite clear clinical indicators—by ensuring continuous, guideline-directed pressure on all modifiable risk factors.

Therefore, the role of nephrology in the continuum of diabetes care is less about crisis intervention and more about long-term, specialized stewardship. It begins with the precise interpretation of microalbuminuria, progresses through the judicious use of RAAS blockers and modern cardiorenal protective drugs, and extends to the management of systemic CKD complications and, when necessary, the careful planning for RRT. The nephrologist provides the essential specialized lens for viewing the diabetic patient through the prism of renal health, ensuring that the critical, silent decline of kidney function is neither ignored nor inadequately treated. This level of integrated, focused care is the definitive strategy for improving both the length and quality of life for the millions living with diabetic kidney disease.

The nephrologist provides the essential specialized lens for viewing the diabetic patient through the prism of renal health, ensuring that the critical, silent decline of kidney function is neither ignored nor inadequately treated.

The specialized intervention of nephrology is the indispensable element that transforms diabetes management from general metabolic control to precision organ protection.